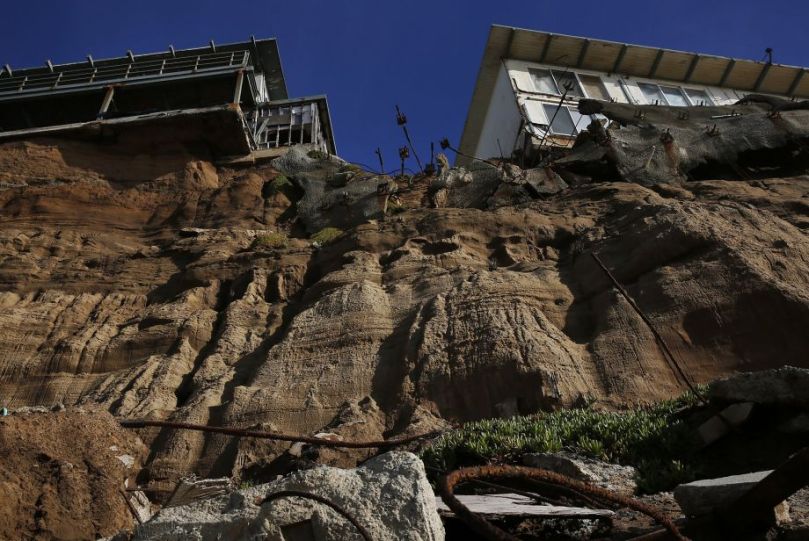

Just a few miles from where I live in San Francisco, the effects of climate change are obvious to everyone. This winter’s record El Nino has brought rain storms that have eroded beach communities along the Pacific. This photo from the San Francisco Chronicle  shows how some of the homes in the city of Pacifica are teetering on the edge of a cliff over the ocean. Scientists are predicting that climate change will bring stronger and harsher El Nino storms in years to come because of the warming oceans caused in large part by human activity. Anyone who reads newspapers or watches news on TV know that this is true, yet somehow many of the Republican candidates who want to lead the country cannot seem to accept the facts.

shows how some of the homes in the city of Pacifica are teetering on the edge of a cliff over the ocean. Scientists are predicting that climate change will bring stronger and harsher El Nino storms in years to come because of the warming oceans caused in large part by human activity. Anyone who reads newspapers or watches news on TV know that this is true, yet somehow many of the Republican candidates who want to lead the country cannot seem to accept the facts.

Climate change is an undeniable fact, yet we still get candidates saying things like this: “If you look to the satellite data in the last 18 years there has been zero recorded warming. Now the global warming alarmists, that’s a problem for their theories. Their computer models show massive warming the satellite says it ain’t happening. We’ve discovered that NOAA, the federal government agencies are cooking the books,” Ted Cruz is quoted as saying that in 2015. Why do some politicians find it so difficult to accept scientific facts?

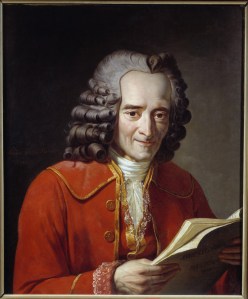

It’s not as though the idea of climate change hasn’t been discussed for years. The medieval idea that the world is unchanging and that human beings have no influence on it was challenged more than 200 years ago by Alexander von Humboldt, one of the

greatest scientists the world has ever known, although much of his work has been forgotten.

Born in 1769, Humboldt traveled to South America in 1800 to explore nature and culture in the Spanish colonies there. When he saw the changes that Europeans has brought to the country by cutting down forests and cultivating lands, he developed his theories of how men affect climate. “When forests are destroyed, as they are everywhere in America by the European planters, …the springs are dried up or become less abundant.” He noted how this allowed the soil to be washed away during heavy rains, causing erosion and a loss of fertile soil

Knowledge is a slow-growing plant, but Humboldt was one of those people who planted ideas that have blossomed during the centuries since he started his explorations. One of the other ideas that he developed in South America was a hatred of slavery, because he saw the cruelty of the European practice of enslaving native peoples. Slowly many of his  ideas have been accepted by mainstream thinkers. Slavery has disappeared in much of the modern world. Let’s hope that more of the climate change deniers will continue to think about the questions and ideas that he raised.

ideas have been accepted by mainstream thinkers. Slavery has disappeared in much of the modern world. Let’s hope that more of the climate change deniers will continue to think about the questions and ideas that he raised.

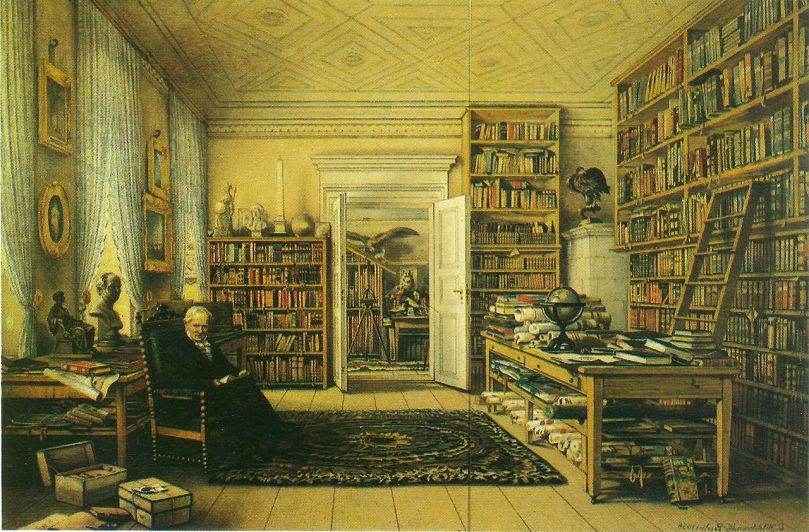

We are lucky this year to have a new biography of Alexander von Humboldt available. Andrea Wulf, has explored Humboldt’s life and ideas in The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World. I highly recommend it to anyone interested in seeing how scientific ideas have developed over the years and learning more about the people who have given us our modern view of the world.