This has been a grim year for many of us. For me and most of my friends, the year  started with a presidential inauguration that we dreaded and feared. As the weeks and months passed, the politics didn’t get any better. Much of public life was tinged with disappointment and a level of discussion more suitable for a TV reality show than for normal social communication.

started with a presidential inauguration that we dreaded and feared. As the weeks and months passed, the politics didn’t get any better. Much of public life was tinged with disappointment and a level of discussion more suitable for a TV reality show than for normal social communication.

As if that weren’t enough, we were plagued by natural disasters—hurricanes hitting Florida, Texas, and Puerto Rico; wildfires in major portions of California—and unseasonable weather in much of the country. The bills for coping with these disasters are still coming in and the suffering of people who lost homes and property will continue well into 2018.

But no year is entirely bad. Each one gives us opportunities for new experiences, encounters with people and with arts that bring us new ideas and emotions. To celebrate 2017, I’ve chosen a few of these encounters that have pushed my ideas in new directions.

Early in the year, I saw the play Leni by Sarah Greenman at the Aurora Theatre in Berkeley. Based on the life of Leni Riefenstahl, the filmmaker who worked in Germany during the 1930s and produced pro-Hitler films such as Triumph of the Will, the play is an exploration of one person’s character. Obviously she is not a sympathetic character, but Greenman’s play shows her as a complicated woman who always insisted that her

interest was in producing art rather than supporting any political positions. The argument is not very convincing, but the play made me think about the tangled motives of real people caught up in world events they cannot comprehend. More than that, this production of Leni was an excellent example of how live theater can make characters come alive with a minimum of background, scenery or narrative. It was a great example of the power of live theater during this period when electronic presentations dominate most art forms.

I had another unexpected vision of an old art form when I went to the exhibit of Gods in Color at the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. As I wrote here a few weeks  ago when I blogged about the exhibit, it may seem trivial to see marble statues presented in a new way, but it made my imagination stretch. It is easy to think about familiar objects as set permanently in time, but it’s good to have our memories shaken occasionally.

ago when I blogged about the exhibit, it may seem trivial to see marble statues presented in a new way, but it made my imagination stretch. It is easy to think about familiar objects as set permanently in time, but it’s good to have our memories shaken occasionally.

One of the most recent books I read, and the one that left me with the most new ideas to ponder was Prairie Fires: A Biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Caroline Fraser. Fraser not only writes a biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, but also gives a portrait of the lives of people who settled the plains states–Minnesota, North Dakota, Kansas, etc.–during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I, for one, had no idea how extremely difficult it was to settle those plains and how the Homestead Act, pushed as a noble deed by the U.S. government, actually encouraged people to settle in areas unsuitable for agriculture. For many people, the move west was a disaster because the plains states were subject to plagues of locusts as well as tornadoes, and extreme weather all of which made it impossible to raise crops profitably. And the farmers did not know that by plowing the plains they were removing the topsoil and thus causing the dust storms that ravaged much of the west during the depression years of the 1930s.

Laura Ingalls Wilder lived through a series of tragedies during her childhood and her early married life–loss of houses to fires and storms, loss of crops, loss of a stillborn baby. Only one child survived to grow up, Rose Wilder Lane, who became a journalist and writer. It wasn’t until Laura Wilder was in her fifties that she started to write. When she did, she found that her daughter was her greatest help in shaping her memoirs for publication, but the relationship between mother and daughter was always contentious. The Little House books grew out of this tangle and eventually became amazingly popular. Their false, cheerful picture of the life of pioneers influenced (and continue to influence) generations of children growing up in the 20th century and are still going strong. The TV shows that were presented in the 1970s falsified the stories even more than the books did and were even more popular.

When Franklin Roosevelt became President, both Laura and Rose became extremely  conservative politically. They were rabid opponents of Roosevelt and the New Deal. Looking back it is almost impossible to believe that innovations, such as Social Security, which have become an integral part of American life were so controversial. Prairie Fires opened my eyes to a new view of American history. I strongly recommend it.

conservative politically. They were rabid opponents of Roosevelt and the New Deal. Looking back it is almost impossible to believe that innovations, such as Social Security, which have become an integral part of American life were so controversial. Prairie Fires opened my eyes to a new view of American history. I strongly recommend it.

Looking back over these experiences that have enriched my life during 2017 gives me hope for the coming year. There will be more performances to hear during 2018, more art to see and, more great books to read. And above all, more new ideas to welcome and ponder.

Happy New Year!

be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.—Mark Twain

be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one’s lifetime.—Mark Twain

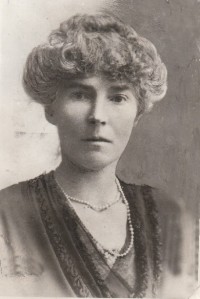

the area. Given the rank of Major—the first woman officer in the history of British intelligence—she caused consternation among other officers who couldn’t figure out how to treat her. But she managed build a comfortable relationship with the men, and she played a vital role in establishing the governments that ruled the Middle East for decades after the war.

the area. Given the rank of Major—the first woman officer in the history of British intelligence—she caused consternation among other officers who couldn’t figure out how to treat her. But she managed build a comfortable relationship with the men, and she played a vital role in establishing the governments that ruled the Middle East for decades after the war.

thought about ancient Greece. Is it possible to see the statue of Socrates as it is shown in this picture and not associate it with austere, intellectual philosophy? Would we think of Socrates in the same way if he were portrayed in an orange or red toga with a busy, bright pattern?

thought about ancient Greece. Is it possible to see the statue of Socrates as it is shown in this picture and not associate it with austere, intellectual philosophy? Would we think of Socrates in the same way if he were portrayed in an orange or red toga with a busy, bright pattern?