When I read biographies of men who have explored exotic countries or started revolutions I’m often more intrigued by the lives of the wives who stand behind them—or don’t stand—than I am of the men themselves. One of my favorites is Sarah Belzoni,  who spent her life following the Italian strongman who became an explorer of Egypt.

who spent her life following the Italian strongman who became an explorer of Egypt.

Giovanni Belzoni was a giant of a man. He was born in 1787, at a time when most European men were about five and a half feet tall, but he stood six feet seven inches. He was smart too. As a boy in Italy, he studied to be an engineer, but when he finished school, Napoleon’s troops were invading Italy, so he was forced to go to England to find work. It wasn’t easy to find work, but he did find a wife, Sarah, who may have been Irish, although no one knows for sure.

Instead of building bridges or roads, Belzoni had to take a job as a strong man in a circus to make money. Audiences gasped when he performed his closing act. He put on a harness fitted with a series of planks on either side of his shoulders. They formed a triangle of planks narrowing toward the top. One by one, other actors would climb up and sit on them. In the finale, Belzoni balanced ten or eleven men on his shoulders as he stood on stage.

Belzoni was ambitious and wanted to be an engineer, not a performer in a circus and Sarah agreed that he should give up the circus. Belzoni worked on his engineering ideas, but he had to keep performing in circuses and fairs to earn a living. He and Sarah traveled to Spain, Portugal and the island of Malta performing but looking for other jobs. In Malta, Belzoni met a man who worked for the Pasha of Alexandria. The Pasha had sent his assistant to Europe to find engineers and other workers who could build modern projects in Egypt. This was Belzoni’s opportunity. He had studied irrigation and had invented a water wheel that would raise water from wells more efficiently than a worker could. He was invited to Egypt to demonstrate his invention.

Giovanni and Sarah Belzoni traveled to 1814 taking with them a young Irishman named James Curtin to help with the work. Day after day Belzoni and Curtin worked building his machine. Some of the Pasha’s workmen worried that the new machine would be so efficient they would no longer have jobs. After four months, Belzoni was finally able to give his demonstration. His wheel pumped more water than the ones being used and it worked faster. It would make sense for the Pasha to install Belzoni’s wheel. Unfortunately, several workmen, who were afraid of losing their jobs, arranged an “accident” that caused James Curtin to get caught in the wheel and break his thigh. After that the Pasha gave up any idea of buying Belzoni’s wheel. Belzoni, Sarah, and James Curtin were stranded in Egypt.

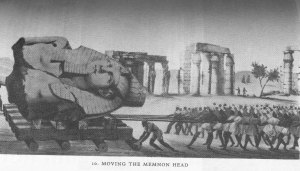

As usual, Belzoni thought of a new scheme. He had heard of a gigantic head lying in the sand near Thebes, a city 700 km south of Cairo. Several European explorers had seen the head and knew how much money it would be worth in Europe, but no one could figure out how to move it. There were no roads in the desert. After the head was dug out of the sand, it would have to be dragged to the river. Then a boat could take it down the Nile River to Cairo and load it onto a ship to England. Belzoni decided he was just the man to do it, but he had to find someone to pay for equipment and workers.

Luckily for Belzoni, Britain had just sent a new representative to Egypt, Henry Salt. Part of his job was to find Egyptian objects for the new British Museum in London. When Salt met Belzoni, he realized had found a strong, adventurous man who could help him. Belzoni told him about his plans for the giant head. Salt provided money and wrote to the Egyptian leaders asking them to help Belzoni move the head.

Belzoni wasn’t sure what kind of equipment he would need for the work. He gathered planks of wood and logs to use as rollers for a cart and found a cheap boat to hire for the trip. On June 30, he set off with Sarah and James Curtin on the long trip up the Nile River to Thebes. By mid-July the group had reached the ruins at Thebes and for the first time they saw the massive head. The stone head had fallen off a statue of the pharaoh Ramses II and was half-buried in the sand. Because no one remembered the name of the pharaoh, the Europeans called the statue Memnon after a Greek hero. Historians believe the statue was toppled during an earthquake in 27 B.C.E. No one at that time knew how large the head was, but scientists later figured out that it weighs seven and a half tons and is 2.67 meters high.

Belzoni needed to hire local men to work with him, but that was difficult. Many Egyptians could not understand why the head would be valuable unless it was filled with gold. Belzoni finally persuaded them he really was willing to pay for their help in digging out the head and moving it to the river. He worked with them to build a flat platform of planks. Then he used other planks as levers to lift the front of the head far enough to get it on the platform. Gradually, using levers and ropes made of palm fiber, they got the head on the platform. Slowly lifting the front of the platform, they inserted one of the logs as a roller underneath and pulled the platform forward.

It took 80 men, working with ropes to insert four rollers under the platform and pull it forward. Each time it moved a few feet ahead, the men would pull out the roller at the back and move it to the front. Slowly, slowly, the head moved forward over the sand and rocks toward the river. Without knowing it, Belzoni had hit upon the same method the ancient Egyptians probably used to move the statue to where it stood. Finally, after twelve days of hard work, but statue was at the edge of the river and ready to begin its journey down to Cairo.

Many women would have rebelled at the idea of living in the blazing desert heat for weeks while their husband struggled with an impossible project, but Sarah didn’t complain. She was very interested in the Arab women of Egypt and spent her time getting to know them. When Giovanni finally succeeded in getting the massive head to Cairo and onto the ship to England, she celebrated with him.

For the next several years Belzoni worked with Henry Salt to collect antiquities, but the number of Europeans traveling to Egypt searching for Egyptian treasures was growing and the competition was keen. Belzoni traveled around the country trying to find objects the British Museum would be willing to buy. When he traveled he often left Sarah behind in whatever lodgings they had found in the city, but she was resourceful and had interests of her own. She took a trip to the Holy Land and she not only went to Jerusalem but traveled by mule to Jericho, Nazareth, and Bethlehem. Before leaving Jerusalem she disguised herself as an Arab merchant and visited the Mosque of Omar, which was prohibited for women and for non-Muslins.

Giovanni and Sarah finally returned to Europe in 1819. Giovanni had become famous, but they still were financially insecure. Giovanni wrote a book about his travels and mounted an exhibition of Egyptian artifacts, some genuine and some plaster copies of statues as well as sketches and pictures Belzoni had made. Sarah helped to organize and publicize the exhibit.

Sarah helped with Belzoni’s book too. She wrote a chapter, called modestly enough, a “Trifling Account of the Women of Egypt, Nubia, and Syria” in which she described the subservient position of women. She noted that Muslim and Christian women led similar lives that were far more restricted than the lives of European women. As the wife of an explorer, Arab men were willing to treat her almost as an equal, offering her coffee to drink and a pipe to smoke. But she was amused to note that they allowed their wives nothing but water to drink and locked the pipes away where women could not touch them. We can only wish that she had written more about her travels and the insights she gained.

Giovanni Belzoni worked hard all of his life, but he died young in 1823 while trying to reach Timbuktu. Sarah lived until 1860 trying to keep Belzoni’s legacy alive, but without much success. The British government finally granted her a pension that kept her from extreme poverty in her old age, but her contributions to her husband’s work and her own personal knowledge of Egyptian life were never acknowledged. She is one of the large group of women who are the indispensible but forgotten wives of famous men.

I nominate the novel “Ahab’s Wife” by Sena Jeter Neslund as a masterpiece of depicting the role of women in history. Although, based on Melville’s novel, the center of the novel is written from the perspective of Ahab’s wife.

One review stated:

“Ahab’s Wife is a novel on a grand scale that can legitimately be called a masterpiece: beautifully written, filled with humanity and wisdom, rich in historical detail, authentic and evocative. Melville’s spirit informs every page of her tour de force. Ahab’s Wife is a breathtaking, magnificent, and uplifting story of one woman’s spiritual journey, informed by the spirit of the greatest American novel, but taking it beyond tragedy to redemptive triumph.”

https://www.readinggroupguides.com/reviews/ahabs-wife-or-the-star-gazer

That sounds like a fascinating novel. I will certainly take a look at it. Thank you for mentioning it.

[…] Sarah Belzoni; Another forgotten wife (en ocasiones parcialmente traducido/partially translated, por su alto interés. […]

Thanks for sharing. I’m reading Unsuitable for ladies by Jane Robinson (about the amazing ly brave and adventurous women travellers of bygone eras) after just finishing Crocodiles on the sandbank by Elizabeth Peters which was funny. Amelia Peabody the main character is a no nonsense victorian feminist lady of means with some witty one liners. So i’d gone looking for the authors inspiration as she was an Expert on Egyptology with a phd from Chicago uni. In the Egypt chapter in Unsuitable for Ladies Robinson made mentioned Sarah in passing “Although Sarah Belzoni when allowed by her Italian scholar husband did indulge ger curiosity somewhat unconventionally” Which made me curious. So thanks for filling in the blanks. Was v interesting.

Makes me want to start planning an adventure.

Yes, they certainly deserve it!

Deep respect to both of them! God bless

I hope you do plan an adventure–and enjoy it!