Trouble is brewing in California over the inequities inherent in having schools subsidized by Parent Teacher Associations which buy iPads, musical instruments and books for school libraries. Sometimes these parent groups pay for music and art teachers to supplement the regular classes. According to an NPR story I heard on the radio last week, some California schools receive an average parent donation of $1000 per pupil each year. Naturally school districts where families cannot contribute money for these extras cannot offer their students equal opportunities. Is it fair in a democracy for wealthier parents to be able to provide extra funding for their own children but not for others? That is a question taxpayers should be asking themselves, but it is certainly not a new one.

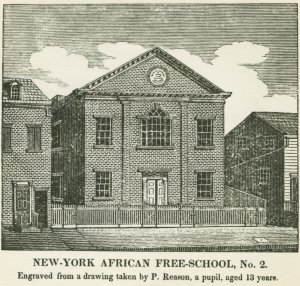

Back in the pre-Civil War days when education for Free Blacks was just starting in the Northern States, a group of women in New York City formed the African Dorcas Society. Slavery was abolished in New York in 1827, and the Black population in the city increased dramatically. Leaders of the Black community, and some white leaders, recognized that the children of these newcomers would need education. Several schools had been established for this purpose, but many families did not send their children to school. The reasons were easy to understand. Not only was children’s labor valuable to the parents, many of whom were struggling, but often the children did not have warm clothing and shoes that would make it possible for them to get to school in bad weather.

Leaders of the Black community, and some white leaders, recognized that the children of these newcomers would need education. Several schools had been established for this purpose, but many families did not send their children to school. The reasons were easy to understand. Not only was children’s labor valuable to the parents, many of whom were struggling, but often the children did not have warm clothing and shoes that would make it possible for them to get to school in bad weather.

The African Dorcas Society was organized by Black women and was one of the first societies in which women met independently and planned their work without the supervision of men. The women divided themselves into sewing circles to make, mend and alter clothing for poor children. They also solicited contributions from well-wishers. For several years the group flourished and supplied clothing to enable children to attend schools. Unfortunately there were many New Yorkers who did not believe that former slaves could or should be educated and there was opposition to the Society’s work as well as the schools themselves.

We all know what happened in the decades that followed, leading up to full emancipation for all American slaves and to the slow establishment of education for all Americans. The struggle still continues to ensure that all children are given the resources necessary for them to attend schools and to take full advantages of education. But during this Black History Month, we should pay special tribute to the multitude of anonymous men and women who worked to make education available to all the children in their community. It’s been a long, hard struggle and it is not over yet. Equal education for all is one of the ideals we have to struggle for every month year after year.

You can read more about how the Black community fought for education and equality during the early 19th century in Leslie M. Alexander’s detailed history African or American? Black Identity and Political Activism in New York City, 1784-1861. It’s a fascinating account of forgotten history.