As I noted in my last blog post, when America’s Founding Fathers wrote the Constitution, they did not address the question of whether women should be allowed to vote. Although Abigail Adams urged them to consider the rights of women, they laughed that idea off. Instead, they turned their attention to a big question the new country had to face—whether or not its citizens should be allowed to own slaves. That issue continued to grow as the 19th century began. And it had an overwhelming impact on the question of women’s rights.

By 1804, the states were almost equally divided between those which allowed slavery and those that outlawed it. The movement to abolish all slavery in America began in the northern states and by the 1820s a number of people in Pennsylvania and New England were speaking out about the evils of slavery. Although almost all Southerners supported slavery, there were a few who opposed it. Among the anti-slavery Southerners, two women stand out—Angelina and Sarah Grimke. They became the only known Southern women to work actively for the abolitionist movement.

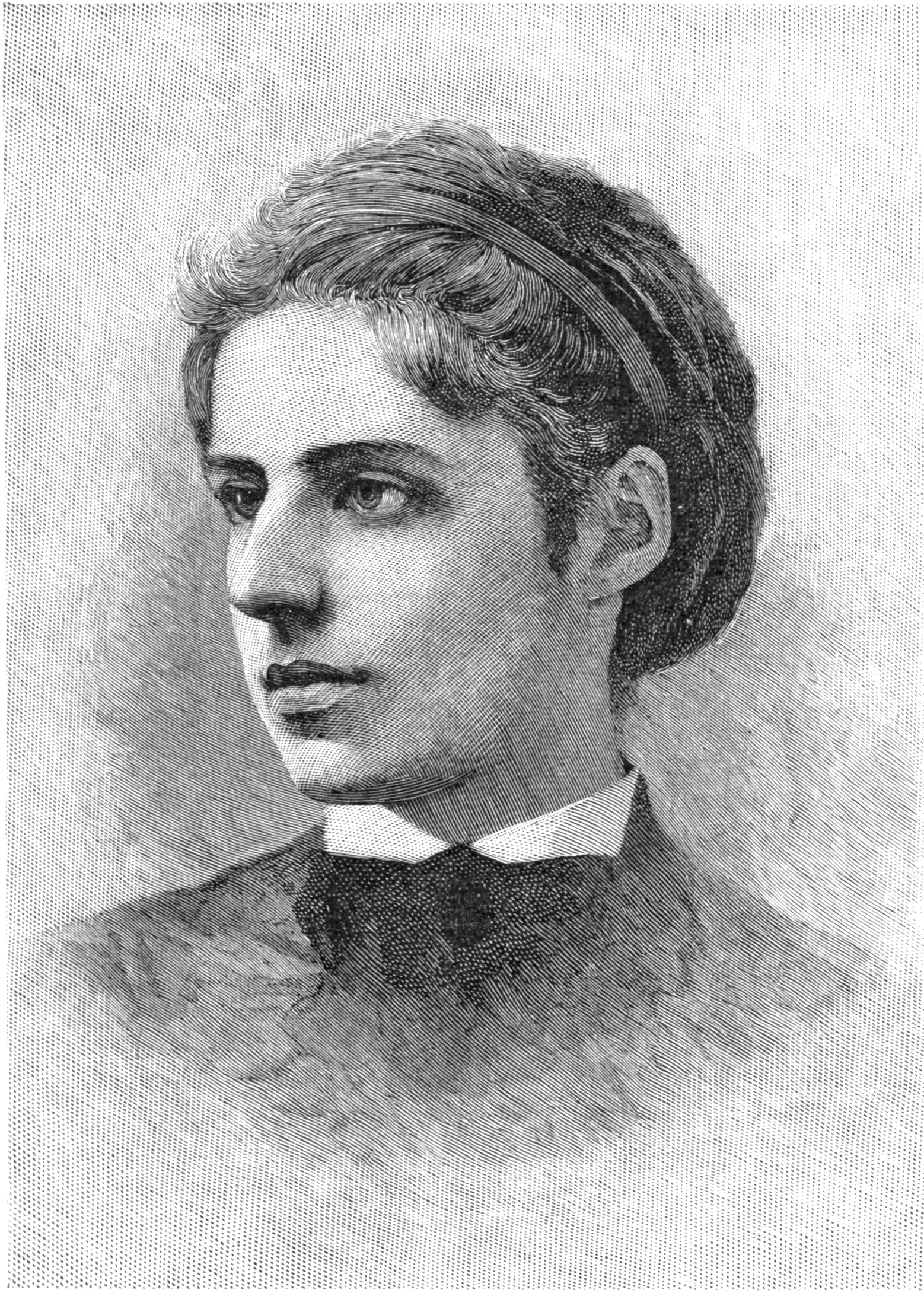

The Grimke sisters were born in Charleston, South Carolina, into a wealthy slave-owning family. Sarah was the older, born in 1792, while Angelina, the youngest of the family’s 14 children, was born in 1805. Although their brothers and sisters accepted the traditional slave-owning views of their family, Sarah and Angelina rebelled. They were both devoutly religious and decided that Christian beliefs were incompatible with owning slaves. Teaching slaves to read was forbidden in South Carolina, but nonetheless the two of them enraged their father by secretly teaching some of their household slaves to read.

Eventually both Sarah and Angelina Grimke decided that living in the South was incompatible with their moral beliefs, so they moved to Philadelphia where they joined the Quakers and became active in the anti-slavery movement. Angelina admired the anti-slavery writings of William Lloyd Garrison, but when she wrote him a letter of support, he published it in his magazine The Liberator. Even though her opinions were compatible with the views of most Quakers, she was disciplined for speaking out without permission.

The idea of women speaking in public, especially when there were men in the audience, remained controversial even in the abolitionist movement. As both Angelina and Sarah Grimke became well known speakers for the anti-slavery movement, they drew more and more criticism. Catherine Beecher, sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, wrote that women should remain silent and let men speak for the cause. In response, Angelina wrote a series of letters to Beecher asking for an explanation of exactly what a woman’s role should be. In one of her letters she wrote:

No one has yet found out just where the line of separation between them [men and women] should be drawn, and for this simple reason, that no one knows just how far below man woman is, whether she be a head shorter in her moral responsibilities, or head and shoulders, or the full length of his noble stature, below him, i.e. under his feet.

None of the traditionalists could answer Angelina’s question to her satisfaction, so the Grimke sisters continued to be active public speakers in the anti-slavery movement. Angelina met her future husband, Theodore Dwight Weld, at an anti-slavery convention in 1836. Although Weld supported the activism of both Grimke sisters, he discouraged them from continuing their public speaking. Nonetheless because the invitations continued to arrive, neither sister completely gave up speaking before both men and women.

In 1838, Angelina spoke about the anti-slavery movement before the Massachusetts Legislature, thus becoming the first woman to address such a body. She also defended a woman’s right to petition as both a moral and political right. Because women could not vote, petitioning a governing body was the only means by which they could influence legislative policy and assert their status as citizens. Over time, Angelina’s speeches came to focus more on women’s rights than on abolition.

After Angelina and her husband had children, she stepped back from public speaking and devoted more of her time to correspondence and taking care of the household. Theodore Weld had serious economic problems, so he and his wife decided to open a school to support their growing family. Sarah moved in with them and both sisters taught at the school.

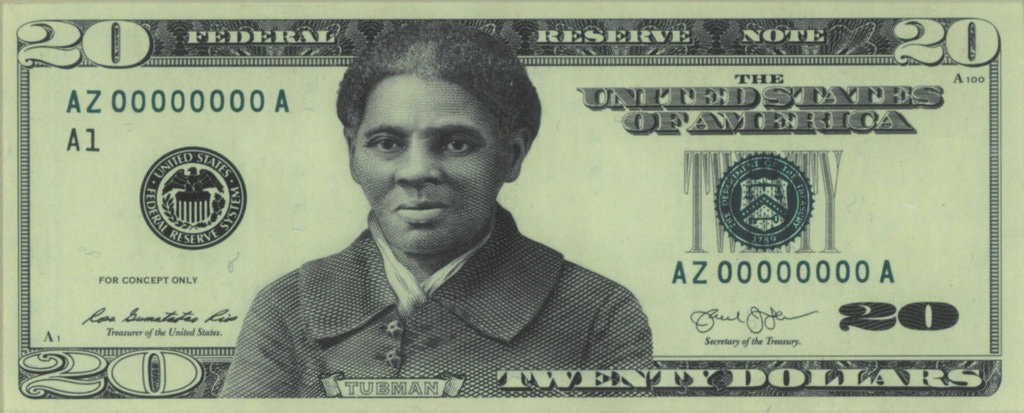

In1870, after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment which stated that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State…”. Angelina and Sarah Grimke took their last public action. Both of them had grown old by this time but nonetheless they made their way to the polls during a blinding snowstorm to cast their votes. Men and boys jeered at them for the attempt, but because they were elderly women, they were not arrested. Neither, of course, were they allowed to vote. Nonetheless at least they had tried.

When the Grimke sisters died, women were still not considered full citizens. That victory would have to wait for younger generations. But in their lifetimes, both Angelina and Sarah Grimke pushed the country a little closer to acknowledging that women should indeed be allowed to be active participants in the country.