Victoria Woodhull’s declaration that she would be a candidate for President of the United States was a bold move that electrified voters in 1870. Two years later, when the presidential election actually came around, everything had changed. Victoria believed she would win because of her strong faith in what her spirits told her, but she didn’t take account of what other people were thinking and doing. During the years 1870-72, the Women’s movement became split into warring groups over policy. Leaders like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton resented the fact that the government gave former slaves the right to vote but refused to do the same for women.  They opposed the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment which gave “all citizens” the right to vote “regardless of race, creed or previous condition of servitude” but did not include women.

They opposed the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment which gave “all citizens” the right to vote “regardless of race, creed or previous condition of servitude” but did not include women.

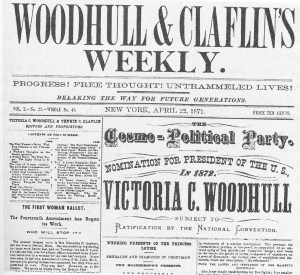

In May 1872, the name of Victoria’s People’s Party was changed to the Equal Rights Party. The party officially nominated Victoria for president and she chose Frederick Douglass, the well-known ex-slave and public speaker, as her vice-presidential running mate. (He later said that he had never heard anything about it.) Both Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Isabella Beecher Hooker supported Victoria’s candidacy, but neither of them believed she had a chance to be president. Because Victoria’s spirit counselors had told her she was destined for high office, she herself firmly believed this would happen. This was the first presidential election in which women’s suffrage was an important issue, because it was the first held after the formation of the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association in 1869.

While the three different suffrage groups were arguing among themselves, the traditional political parties also struggled over their candidates. Ulysses S. Grant, a Republican, was seeking a second term, but the so-called Liberal Republicans split from the main party and nominated Horace Greeley, founder of the New York Tribune. Greeley also got the Democratic nomination. After the turmoil of nominations the campaign itself was one of the most bitterly-fought campaigns in American history.

Victoria’s unquestioning faith in her spirits led her astray when it came to politics. In the end it wasn’t the search for voting rights that brought her down, it was the familiar question about sexual purity and scandal. Victoria and her sisters had lurid pasts compared to those of the other women leading the suffrage movement, but these respectable women also had many secrets to hide. The intrigues and infidelities of leading male citizens touched the lives of their wives as well as their mistresses. Henry Ward Beecher, a distinguished minister and civic leader, was especially vulnerable. His sister Isabella Beecher Hooker was one of Victoria’s strongest supporters, but when rumors about her brother started circulating, she was torn. Unfortunately, Victoria, because of her friendships with brothel managers and prostitutes, knew many of the most scandalous stories in New York.

Victoria Woodhull believed in sexual freedom, as many of the suffragettes did, but she practiced it more than many others. This made her vulnerable to political opponents who spread stories about her and pilloried her in the press. Thomas Nast in his cartoons made her a special target as “Mrs. Satan”. After that cartoon appeared Victoria’s political life was dead. Her speaking engagements were cancelled and her supporters fled to other candidates. Embittered by the desertions, Victoria finally printed an article revealing the affairs of Henry Ward Beecher and other leading citizens. This is what led to her arrest and was the reason she spent Election Day in jail rather than at the polls. Some of the women’s suffrage leaders did attempt to vote; Susan B. Anthony cast a ballot, but her vote was not counted and she was given a $100 fine for the attempt. The election which seemed to promise vindication for women’s rights proved to be a miserable failure for them. The struggle continued for another fifty years.

Today, as we look back from the enormous new freedoms in sex and marriage that have been gained over the last hundred years and more, it’s hard to know what to think of Victoria Woodhull. She pioneered many of the ideas we now accept as desirable. Who would go back to the bad old days when women weren’t allowed to vote or manage their own money or divorce their husbands and keep custody of the children? At the same time, we have to admit that Victoria would have been a terrible president. Going into trances and listening to the voices of spirits got her a long way, but they probably wouldn’t have provided a clue about how how to reconcile the North and South after the long destruction of the Civil War. We can admire her spirit in making public some of the sins of hypocrites who were running the country, but we have to admit that her unsavory activities (and her disreputable family) set back the suffrage by decades. Women didn’t finally get the vote in the United States until the passage of the 19th amendment 1920.

If you have become as fascinated by this tumultuous period in American history as I have, you may want to read Barbara Goldsmith’s book Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull. It covers the period thoroughly and gives an amazing account of the character and lives of some of the men and women who made America the country that it is today.