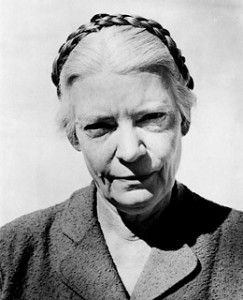

Reading about other people’s lives is one of my favorite activities. Who needs fictional accounts of fantastic worlds when the real world offers so many fascinating stories? Often it’s not the lives of people who had brilliant successes that affect me most; it’s the people who didn’t quite make it. May Alcott was one of these. She was the “sister of the more famous Louisa” as family historians might say.

There were five Alcott daughters. Louisa grew up to be a famous author. Her book Little Women gives readers a glimpse of the lives of the Alcott sisters. In the book they are called the March sisters and the youngest, called Amy in the book, was modeled on May Alcott. Amy loved art, just as May did, but her life was more exciting than the one Louisa put into the book.

May Alcott was born in Concord, Massachusetts on July 26, 1840 to Bronson and Abigail Alcott. As a young child she lived in the community Fruitlands, which her father had started. The rules were strict—no animal food, not even milk for two-year-old May. When her mother tried to milk the cow, her father decreed, “We don’t allow milk on this farm. Pure water is the best drink for all God’s creatures.”

“Why can’t we live the way other people do?” his wife protested. That question was one young May Alcott would ask often as she grew older, and she never found an answer.

As May grew up she was independent and ambitious. Most of her friends thought only about getting married, but May had different ideas. She was determined to earn money herself and not depend on a husband’s support. It would not be easy to support herself as an artist. Many girls studied art but when they grew up, they were expected to get married and let their husbands earn money. Professional artists were almost always men. May studied art in Boston, and she gave art lessons, but made so little money that she had to turn to teaching.

As May grew up she was independent and ambitious. Most of her friends thought only about getting married, but May had different ideas. She was determined to earn money herself and not depend on a husband’s support. It would not be easy to support herself as an artist. Many girls studied art but when they grew up, they were expected to get married and let their husbands earn money. Professional artists were almost always men. May studied art in Boston, and she gave art lessons, but made so little money that she had to turn to teaching.

May’s life was dramatically changed by the success of Louisa’s book, Little Women. Now there was money for new clothes and books and even travel. For years May had longed to study art in Europe. The great museums and picturesque castles, churches, and cities of Italy and France were unlike anything in America. May had never seen famous paintings or statues. She had never even seen photographs of them. Instead, she had learned about European paintings by looking at copies made by Americans who traveled abroad. Some of the copies were good, but they were only small imitations of what the artist had created. Now at last she would be able to see the glowing colors of the originals. Louisa had been in Europe once before, when she had traveled as a paid companion to an ill elderly woman, but they had done little sightseeing. She wanted to return to Europe and spend leisurely time introducing May to the places she had seen briefly before.

Two years after the publication of Little Women, Louisa finished writing An Old Fashioned Girl. Now the two sisters had their chance to travel. On April 2, 1870, May and Louisa and their friend Alice Bartlett sailed to France. Everything was different from what they had been accustomed to in New England. Instead of fresh white clapboard houses, they saw homes, some of them centuries old, built of stone. Instead of simple wooden churches, they saw shadowy cathedrals with statues, candles, and stained glass windows. May carried her sketchbook everywhere, always ready to capture the changing sights that surprised her so much.

The study years in Europe were May’s happiest times, but she and Louisa could not remain there long. Their mother was growing old and ill; their sister Anna’s husband died. Louisa went home first to help out and then May followed. For the next several years family responsibilities tied May down. It wasn’t until 1876 that she had a chance to return to France.

The study years in Europe were May’s happiest times, but she and Louisa could not remain there long. Their mother was growing old and ill; their sister Anna’s husband died. Louisa went home first to help out and then May followed. For the next several years family responsibilities tied May down. It wasn’t until 1876 that she had a chance to return to France.

This time, May went directly to Paris where she joined two friends from home, Kate and Rose Peckham. The three of them settled into comfortable lodgings and arranged for art lessons. Suitable art classes for women were not easy to find because art students learned to draw people by having live models in class. For many people the idea of women looking at people who were nude or lightly clothed was shocking. Even worse was the idea of having men and women in the same class looking at these models. Because of this, many of the famous art schools in Paris did not accept women. May was disappointed, but she made the best of her situation. She found a teacher, Monsieur Krug, who solved the problem by accepting only women in his classes.

Not only was May a successful student, but one of her paintings was chosen from among the thousands submitted for the Paris Salon exhibit of 1877. May was eager to share her triumph with her family. No longer would Louisa be the only successful Alcott. May wrote to her mother:

Who would have imagined such good fortune, and so strong a proof that Lu does not monopolize all the Alcott talent. Ha! Ha! Sister, this is the first feather plucked from your cap, and I shall endeavor to fill mine with so many waving in the breeze that you will be quite ready to lay down your pen and rest on your laurels already won.

When the first viewing day of the Salon arrived, May went very early to see how her picture was hung. She found it was dwarfed by the huge canvases around it, but thought it held its own because the hanging committee had placed it at eye level where everyone could easily see it. Many of the artists and visitors complimented her on her painting. She felt very festive in her fashionable black silk dress and was surprised at how easily she mingled with the smart, artistic crowd. At last her patience and persistence were being rewarded. After years of being a student, she was finally being recognized as a real artist. She moved to London to pursue her career.

Meanwhile in Concord, the Alcott family was struggling with May’s mother’s failing health. Louisa wrote to urge May to come home and spend some time with her mother. May was torn between wanting to return to Concord and longing to stay abroad. She knew her mother missed her, and she wanted to be with her family at this difficult time. One day she walked to the steamship office to buy a ticket to sail to America, but when she got to the office, she turned back. She was afraid leaving Europe would mean giving up all her artistic hopes. Her dream was to return home with a strong record of artistic achievement to make her mother proud.

In November, that dream ended when May received word that her mother had died. She was overwhelmed with grief and felt guilty about her decision to remain in Europe. Although American friends were kind and helpful, May spent most of her time alone. She avoided people who came to express their sympathy, because she found it difficult to talk about her mother without crying. Instead, she took long walks through the dark, rainy London streets and spent hours in Westminister Abbey listening to organ music. She wrote to Louisa, “I try to do as she would have me and perhaps shall work the better for the real suffering I never knew till now.”

One of her boarding house friends was a young Swiss businessman named Ernest Nieriker. During the darkest days of her grief, she could hear him playing the violin in his room across the hall from hers. He knew the music cheered her, so he would leave his door open as he played. He also offered to read to her in the evenings when her eyes were tired, or to play chess with her. He and May soon became close friends and their friendship slowly turned into love. Although he earned his living in business, Ernest was deeply interested in both art and music. May found him very congenial, and he encouraged and appreciated her work.

By March, there was another artistic triumph to celebrate. May had two pictures accepted at the Ladies Exhibition in London. But soon she had an even greater event to write home about. Ernest asked her to marry him! He was several years younger than she was, but they shared a love of music and art. Best of all, Ernest encouraged May to continue her artistic career.

May’s father and sisters were astonished at this sudden engagement, but even more startling news was soon to come. Within a few days of their engagement, Ernest received unexpected news. He would have to leave London for at least a year to work for his business in either France or Russia. May and Ernest were unhappy at the thought of being separated for such a long time and Ernest made a bold suggestion:

Why should we not have this year together? Life seems too short to lose so much. If you will consent to forego a fine wedding and fine trousseau and begin with me now, we can enjoy so much together.

And so May’s life took another turn for the better. The young couple was very happy and soon May was pregnant. She looked forward to having a child and to continuing her artistic career with Ernest’s help. Once again things went wrong. May did not survive the childbirth, although her daughter did. May’s life was cut short and she was never able to fully realize her talents and achieve her goals. To me she is still a heroine because she faithfully pursued her goals and tried to achieve success without sacrificing her family or the people she loved. That’s why she is my Woman of the Week.