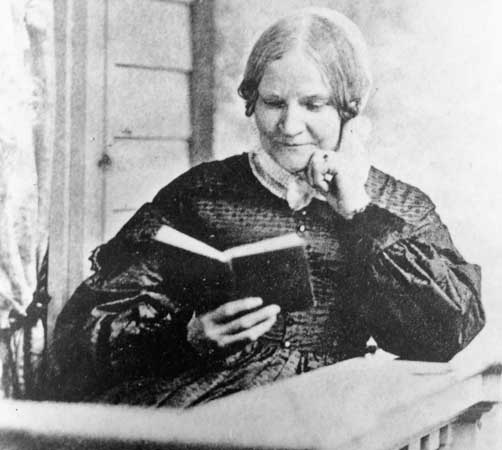

Lydia Maria Child once explained the secret that made her life productive. In a comment about housekeeping she wrote “The true economy of housekeeping is simply the art of gathering up all the fragments, so that nothing be lost. I mean fragments of time, as well as materials.” Child spent her life finding fragments of time and using them to make life better for herself, her family, and her country. For her entire long life, she turned those fragments into articles and stories that she hoped would eradicate the cruelty of slavery and the injustice of life in America during the 1800s. And yet now her name is almost forgotten. How did that happen?

Child was born Lydia Maria Francis in Medford, Massachusetts on February 11, 1802, to Susannah and Convers Francis. Like most girls at that time, she did not receive much formal education, but an older brother, Convers Francis, noticed that she was an avid reader and he enjoyed sharing his books with her. When he left home to attend Harvard, the two of them carried on a lively correspondence. After her mother died, Lydia moved to Maine to live with an older, married sister and train to be a teacher.

Eventually Child was able to move to Boston to live with her brother Convers who had become a Unitarian minister. There she met many of the intellectual and cultural leaders of the day. She discarded the name “Lydia” that she had always hated and from that time on chose to be known as L. Maria. Her urge to write led her to try her hand at an historical story and in 1824, she published her first book, Hobomok, an historical novel about a native American Indian in New England who married a white woman. Although some readers objected to the theme of interracial marriage, many others admired the book and she soon found a wide audience.

As her confidence grew, Child realized that she could use her practical knowledge to improve the lives of American women who were keeping house and raising children in a new country. She started a journal called The American Practical Housewife, which became one of the most popular publications of the 19th century. Her recipes and housekeeping tips were valued as was her advice on raising children. She soon added another journal, The Juvenile Miscellany, filled with stories and poems designed for children.

Among Convers Francis’s friends was a young lawyer, David Child, who admired L. Maria’s writing and soon began courting her. Like Maria and her brother, Child came from a middle-class family of limited means. He had attended Harvard but had no wealth or property to support himself while he struggled to make a living as a lawyer. David was definitely not a good marriage prospect for a young woman who had no family wealth of her own, but the two shared a deep commitment to making the world a better place. So, like so many young lovers, they decided their love would conquer all. They married in 1828, determined to build a better world.

Both of the Childs were ardent supporters of William Lloyd Garrison and read his newspaper The Liberator. Both of them followed Garrison’s lead in proposing that enslaved people should be freed immediately and given compensation from their owners for their years of labor. While more conservative Americans suggested that freed slaves should be sent to Africa to build new lives in the home of their ancestors, David and Maria Child wanted them to remain in America and gradually merge into a new life through education and intermarriage. Like most of the people who supported the abolition movement during the 1830s, neither David nor Maria could foresee what a long, slow, and bitter process it would be to end American slavery.

Although both of the Childs remained committed to the reforms they supported, their lives did not work out as they had planned. David’s career as a lawyer was never successful and he piled up debts as he continued to try to build a practice. He even spent a short time in jail because of his failure to pay off debts. Lydia Child wrote articles and books to support the two of them, but as a woman, all the money she earned from her writing belonged to her husband. The couple never had any children, and at times they lived apart, but they remained devoted to each other.

Maria Child’s practical articles about housekeeping were popular, but she was not content to write only about domestic issues like making soap and choosing fresh eggs. She was determined to help in the struggle to free slaves and women, two groups that she saw as being exploited by men who treated them as property. Some readers rejected her outlook. The book that lost her the most readers was her An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans. In it she advocated the abolition of slavery but rejected the notion of sending freed slaves back to Africa. Instead, she wanted to integrate them into American society and make them the equal of white citizens. She accused Northerners of being just as racist as Southerners, which infuriated some old friends and other leading citizens of Massachusetts. She believed in education and in intermarriage. She wrote:

An unjust law exists in this Commonwealth, by which marriages between persons of different color is pronounced illegal. I am aware of the ridicule to which I may subject myself by alluding to this; but I have lived too long, and observed too much, to be disturbed by the world’s mockery. In the first place, the government ought not to be invested with power to control the affections, any more than the consciences of citizens. A man has at least as good a right to choose his wife, as he has to choose his religion.

The struggle to abolish slavery took far longer than most reformers had expected. It was not until a Civil War threatened the future of the country that the Emancipation Proclamation was finally passed and slavery ended. And even then, the struggle continued. Lydia Maria Child continued her writing and her work for justice until the end of her long life. She died on October 20, 1880.

A good place to learn more about Child and her fascinating life is the recent biography Lydia Maria Child: A Radical American Life by Lydia Moland (Univ. of Chicago Press 2022). It is available in most public libraries and in bookstores as well as online.