Emily Carr was a precocious artist—when she was a child she surprised her parents by drawing the family dog, “I sat beside Carlow’s kennel” she writes in her autobiography, “and stared at him for a long time. Then I took a charred stick from the grate, split open a large brown-paper sack and drew a dog on the sack.” Emily was eight years old at the time. Her talent was obvious to her parents from that picture and so she was allowed to study drawing, but both of her parents died while she was young and there was little encouragement for her to do anything except to follow her sisters’ examples and prepare for marriage and families. Her path to becoming a recognized artist was long and difficult. As a teenager she persuaded her guardian to let her go from the family home in Vancouver down to San Francisco to study art, but later she returned home and gave up painting.

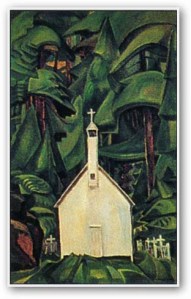

For several years she pursued an eccentric life, keeping a boarding house to earn money and to pay for a menagerie of animals as pets. Her family, she believed, were stuffy and conventional and limited her artistic possibilities. She spent years, which grew into decades, in pursuit of skills that would allow her to become the artist she wanted to be She had a passion for the natural world around her in western Canada. As a child she rode a pony into the woods where she marveled at the sights and sounds around her. On a trip to Alaska in her twenties she discovered the arts of the Native peoples of the Northwest and the towering totem poles they carved. All of these sights would eventually fuel her art, but it was a long time before the transformation began.

For several years she pursued an eccentric life, keeping a boarding house to earn money and to pay for a menagerie of animals as pets. Her family, she believed, were stuffy and conventional and limited her artistic possibilities. She spent years, which grew into decades, in pursuit of skills that would allow her to become the artist she wanted to be She had a passion for the natural world around her in western Canada. As a child she rode a pony into the woods where she marveled at the sights and sounds around her. On a trip to Alaska in her twenties she discovered the arts of the Native peoples of the Northwest and the towering totem poles they carved. All of these sights would eventually fuel her art, but it was a long time before the transformation began.

Vancouver was on the outskirts of the art world of the time—the turn of the twentieth century—and Vancouver was so far outside the center that Carr was not aware even of the art being produced in Toronto and the rest of Ontario. She became discouraged about her painting and even after she had a chance to study for a while in Paris, she still did not feel that she was capable of being an important artist. She suffered from the familiar female feeling that artists were men, and many of the male artists she met were content to patronize the women who attempted to become part of the art world. Then at last she met the artists who would open the world for her.

The Group of Seven painters who worked mainly in Ontario were Canadian artists who had found a new way of presenting the beauty of the North to others. Lawren Harris, in particular, became a mentor to Emily Carr and helped her to see that the pictures she was struggling to make of Northwestern Canada and the Indian life there were worth doing. When A.Y. Jackson, another member of the group, told her that “Too bad, that West of yours is so overgrown, lush—unpaintable,” Harris told her to keep faith in what she was doing. When she went back to Vancouver, she was able to continue and in the last decades of her life produced works that have lasted. Even though they are not yet as well known outside of Canada as they deserve, those of us who see them believe that Emily Carr may have been a late bloomer, but her work will live long.

Anyone who is interested in knowing more about Carr’s life should read her autobiography “Growing Pains”. She tells a good story and for a reader who wants more detail and more objectivity, there are several good biographies to choose from Best of all, however, try to see her paintings, either in person or in the reproductions available online and in print.